-

Here

- Home >> News >> Company News

Here

This time two years ago, electronics industry forecasters were projecting 2020 would be a banner year for the electronics industry after the roller-coaster ride of strong growth in 2018 and a slump in 2019. A case in point was the 5.9 percent semiconductor growth rate for 2020 by the World Semiconductor Trade Statistics (WSTS) based in part on expectations that the scheduled rollout of 5G infrastructure would accelerate and feed the digitization-of-everything trend in many end markets.

It was not to be. Instead, we got the Covid-19 pandemic that shuttered factories, offices, and airports and transformed work, school, and daily life. As a result, global GDP growth for 2020 was a stunning negative 3.1 percent, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). U.S. GDP growth was even worse at a negative 3.4 percent. The World Bank pointed out that 2020 was the fourth deepest recession since data was first collected in 1870.

What a difference a year makes. The IMF is projecting a rebound in 2021 for global GDP growth of 5.9 percent and 5.2 percent for the U.S. posting. However, both will moderate in 2022 to 4.9 percent for global GDP and 4.5 percent for the U.S.

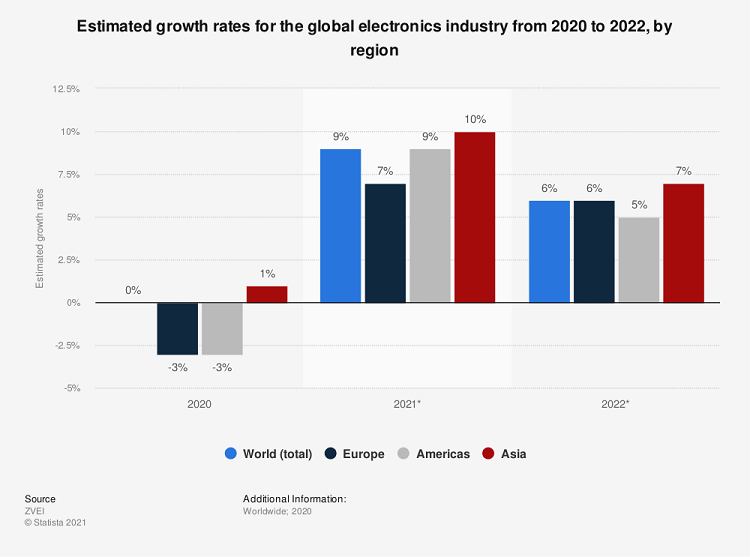

Source: Statista

Global growth in the electronics sector was zero in 2020, with the U.S. and European electronics sectors posting negative 3 percent growth and Asia growing a paltry 1 percent. However, despite the continuing supply chain woes, Statista is projecting a rebound for this year in the high single digits and moderate single-digit growth in 2022.

Covid

There are a few reasons to take the 2022 projection with a grain of salt. First, the new omicron Covid variant is spreading rapidly, and low vaccination rates in much of the world suggest infections will persist well into the new year, perhaps beyond. Also, there’s always the possibility that yet another Covid variant will emerge, disrupting production and supply chains.

Cold war

More concerning is the elephant in the room: the growing tension between China and the U.S. In October, 38 Chinese warplanes flew over Taiwan, testing the island state’s air defenses. In November, American aircraft carried out 94 reconnaissance flights over the South China Sea near the Chinese coast, according to the South China Morning Post.

Less than 8 percent of Taiwanese citizens favor unification with mainland China, according to a survey by Taiwan’s National Chengchi University in June 2021.

“We have entered a cold war with China,” said Dale Ford, Chief Analyst, Electronic Components Industry Association (ECIA). “The goal now is to avoid a hot war.”

China denies its intention to bring Taiwan back into the fold, as it did with Hong Kong earlier this year. But the threat looms large not only in terms of souring U.S.-China relations but in the control of the world’s most valuable intellectual property: bleeding-edge semiconductor manufacturing process technology.

Supply chain

While parts shortages have improved from the crisis earlier this year when automakers were forced to shut down production lines, they remain a challenge. According to the ISM® November Purchasing Managers Index (PMI®) report, “The U.S. manufacturing sector remains in a demand-driven, supply chain-constrained environment, with some indications of slight labor and supplier delivery improvement.”

Industry segments reported “record-long raw materials and capital equipment lead times, continued shortages of critical lowest-tier materials, high commodity prices and difficulties in transporting products,” according to ISM®.

Many of the parts and raw materials are sourced from Asia, prompting OEMs and Tier-1 manufacturers to take steps to secure key manufacturing partners and suppliers located in North America. This includes encouraging foreign suppliers to set up operations in North America and recruiting home-grown North American companies. For example, Ford Motor Co.’s decision to partner with New York-based Global Foundries for semiconductors will protect Ford from supply chain disruptions of sourcing from companies on the other side of the planet.

In part to mitigate the looming threat of China’s regional hegemony, Taiwan’s TSMC, South Korea’s Samsung, and Intel are exploring plans to build new fabs in the U.S. and Europe that could come online as early as 2023, according to the ECIA’s Ford.

Inflation

Shortages of components drive up prices, which lead to higher finished goods prices for the end customer. Earlier this year, inflation was viewed as a short-lived phenomenon due to supply chain challenges. However, the thinking now is that inflation will be more enduring. The OECD is projecting consumer-price inflation in the US to average 4.4 percent in 2022, up from 3.1 percent, which is forecast to moderate down to 2.5 percent in 2023. Both years are higher than the 2 percent target set by the US Federal Reserve.

Contributing to the inflationary trend are Covid-related issues such as worker absenteeism, short-term shutdowns due to parts shortages, difficulties filling open positions, and overseas supply chain and transportation issues that limit manufacturing’s growth potential.

The fear is that consumers and businesses will postpone purchases, which will erode demand for components and slow economic growth.

Chip shortage

Perhaps the most challenging and costly consequence of the Covid pandemic has been the chip shortage, a result of waves of factory closures and fab shutdowns in 2020 and reopenings in 2021, most notably in the automotive industry. These erratic swings exposed the limits of the just-in-time inventory best practice, forcing manufacturers to shift to the old-school “just-in-case” inventory approach. Consequently, customers stockpiled and double-ordered semiconductors and other electronic components, which reduced visibility into the actual state of supply and demand.

Exacerbating the situation, semiconductor companies are not expanding production to the degree seen in previous cycles, partly because they’re concerned about capex and the speed of technological change.

Still, the semiconductors sector is poised for growth in 2021 and 2022. According to the WSTS Fall 2021 global semiconductor sales forecast, worldwide chip sales for 2021 will reach $553 billion, a 25.6 percent increase from $440.4 billion in 2020. Regionally, Asia Pacific leads the way with 26.7 percent annual growth, followed by Europe (25.6 percent), the Americas (24.6 percent), and Japan (19.5 percent). For 2022, WSTS is projecting a more modest annual semiconductor growth of 8.8 percent, topping $600 billion in worldwide annual sales.

Market researchers agree that the chip shortage crisis will be with us through at least mid-2022 when fab lines come back online, and supply and demand visibility improve. At the same time, the U.S. and European independent design manufacturers (IDMs) are expected to be online by mid-2022, resulting in component oversupply and another round of supply chain readjustments.

By 2025, chip shortages and trends such as electrification and autonomy will drive 50 percent of the top 10 automotive original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) to design their own chips, according to Gartner Inc. As a result, they will gain greater control over their product roadmaps and supply chains.

“Automotive semiconductor supply chains are complex,” said Gaurav Gupta, research vice president at Gartner. “In most cases, chipmakers are traditionally Tier 3 or Tier 4 suppliers to automakers, which means it usually takes a while until they adapt to the changes affecting automotive market demand. This lack of visibility in the supply chain has increased automotive OEMs’ desire to have greater control over their semiconductor supply.”